The Culture of Divide

Roeland Decorte.

Through centuries of vague

characterization, deliberate misrepresentation and manipulation of our innate tendency to consider

the world through an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ narrative, society in the West has

become heavily dichotomized. Indeed, we

are living in a time when political divisions, enmities and feuds are no longer

limited to localities or individuals, but carry on, throughout time, from one

generation to the next, bringing with them a premade set of ideals, hopes and

beliefs, as well as vilification of the other side. In this post I will briefly

argue why the use of terms such as ‘left’ and ‘right’-wing, as well as most

terms like ‘progressive’ or ‘conservative’, are not only futile in reasoned

political debate but actually actively harmful and obstructive.

The

History

In the early days of

the French revolution, the “Assemblée

nationale” – the transitional government – was divided into those in favour

of the revolution, and those in support of the old monarchy. The

revolutionaries sat to the left, whereas those in support of the old order were

seated on the right. Though during the days of executions and arrests the right

side was often abandoned, the seating arrangement survived in later

governmental structures. In the successors of the Assemblée, the so-called ‘innovators’ were nearly always seated on

the left side and the so-called ‘defenders of the constitution and faith’ on

the right.

|

| The Assemblée nationale |

The idea of a

‘left-right’ division fitted well into the storm of political ideals overtaking

Europe in the late 18th and 19th century after the French Revolution. The notion of a world-wide class struggle

between the people as a whole and its ‘higher orders’ grew exponentially. And indeed, in those days there were actual entrenched

political classes: the aristocracy still dominated the political landscape of Europe and

the population as a whole had very little say in government. Following the

seating arrangement of the French parliament, the term ‘left-wing’ became known

as ‘progressive’ – consisting mainly out of ‘commons’ – whereas ‘right-wing’

became known as ‘conservative’ – consisting mainly of the aristocracy.

Road

to Nowhere

Whatever original

usefulness these terms might have had for the characterization of different

sides during the French revolution, as well during the subsequent European struggle

against the aristocracy, I need not point out to anyone familiar with the

current political landscape that the terms have long since lost their meaning. With

the disappearance of an actual aristocracy with political power, the terms are

now used in a myriad of different ways, with a myriad of different – often

contradictory – meanings. In our current representative democracies, not one

major party proposes a reinstatement of aristocratic rule (though some propose

bureaucratic, or ‘technocratic’ rule) and all sides – at least nominally but

hopefully also genuinely – believe in the right of the people to govern

their own affairs.

The ‘right-wing’ as it

existed during the French revolution, therefore, no longer exists. Nor does, in

fact, the French revolutionary left, as it was a mixed bag of what later would

become defined as liberalism (meant in the original interpretation, not the new

American one), socialism and centrism. Indeed, both the

current ‘left’ and ‘right’ were born from what was ‘liberal’ opposition to

traditional aristocratic rule. Really, what we now see as the difference

between left- and right-wing politics is a split following the division in the mid-19th

century between capitalist and anti-capitalist movements. The fact that

this is where the real modern division gets its first inception is best illustrated by the fact that ‘classical

liberalism’ is deemed to be right-wing, whereas ‘social liberalism’ is deemed to be left-wing.

|

| Inauguration of the Statue of Liberty |

Divide

et Impera

Of course one could

argue that the terms have evolved with time, and though none of the original premises

hold true, the populace generally understands what is meant by ‘left’ and

‘right’-wing by observing political practice. As we will see below, however,

this does not seem to be the case at all.

A very in-depth

study conducted over the course of multiple years by the London School of

Economics as part of the official British

Election Studies found that, when asked to place themselves on the left-right

scale, just

over 18% of voters did not know what ‘left-wing’ meant. Of the remaining 82%,

each gave roughly two answers. From all of these answers only 59 per cent could

be said to ‘correspond unambiguously with even a broad-based conception of what

political scientists mean by ‘left’ (that is, answers which said that ‘left’

meant in favour of working-class, poor, ordinary working person or against the

middle class, the rich or business; answers which associated the left with

Communism, Marxism, socialism, the Labour Party, or against Conservatism,

fascism, etc.)’ [Heath and Lalljee 1996: 98].

The study also noted

that ‘among the most common answers (given 45 times) were ones which defined

the left as people who are extreme, dogmatic or militant but without any

mention of the content of their extremism’ [Heath and Lalljee 1996: 99] – a

fact, I would argue, clearly illustrative of the divisive nature of the

left-right divide. On what was meant by ‘right-wing’ politics, there was again

just under 20% of respondents that did not know the answer. The remainder gave about

1.2 answers per person, of which only 58% corresponded closely to the political

scientist’s concept’ [Ibid].

Methods

define the Results

The motto of this establishment

– often consisting of self-styled ‘technocrats’ – is simple: ‘people cannot

think for themselves, therefore we must decide what is best for them.’ This,

they say, is proven by data such as the study quoted above: people do not know what

they want, or what is the best way to go about to achieve it.

Indeed, much previous

research done in the line of the paper above (most notably Butler and Stokes'

seminal work) seemingly observed the general population to be perpetually fickle

in its allegiances and beliefs – often displaying little to no knowledge of the

issues, voting based on arbitrary notions such as who their family 'always voted for’ or which politician's personality they liked. These studies then often ended by noting that the only conclusion one could draw was to ‘interpret the

fluidity of the public’s view as an indication of the limited degree to which

attitudes are formed towards even the best-know policy issues.’ [Butler and

Stokes 1974:281] Such sentiments remained dominant amongst political scientist

for decades, and were very convenient for those in favour of more

centralization and less direct popular involvement.

The paper quoted above, however, [Heath and Lalljee 1996] explored the

possibility that the problem actually was not the intelligence or

involvement of the general populace but rather the models used to map political

preference. Their paper was not the first paper to identify problems with the two-dimensional mapping of political opinions [see Luttbeg and

Gant 1985; Himmelweit et al. 1985; Heath 1986a; Fleishman 1988]. In their research,

however, they did not only inquire into the flaws of the model, but also

demonstrated that, when using different models, people in fact appear

consistent in their beliefs and ideals, as well as heavily involved in political issues.

The paper quoted above, however, [Heath and Lalljee 1996] explored the

possibility that the problem actually was not the intelligence or

involvement of the general populace but rather the models used to map political

preference. Their paper was not the first paper to identify problems with the two-dimensional mapping of political opinions [see Luttbeg and

Gant 1985; Himmelweit et al. 1985; Heath 1986a; Fleishman 1988]. In their research,

however, they did not only inquire into the flaws of the model, but also

demonstrated that, when using different models, people in fact appear

consistent in their beliefs and ideals, as well as heavily involved in political issues.Rather than using the one axis left-right identification, they offered another, that of authoritarian vs. libertarian. But most notably, they chose to ask people about specific political beliefs rather than just party-political issues or current affairs. This is crucial, as it serves to briefly break through the bonds of the partycratic politics dominating our modern representative democracies, and tap right into the personal beliefs and hopes of the individuals.

The study asked the

interviewees for their opinions on things like big business, freedom of speech,

tradition and the legal system. and then asked the same group the same question

again one year later. Subsequently they used these specific issues to predict how the interviewees would vote in particular elections.

Unsurprisingly, this model

yielded a stunning consistency in political beliefs and hopes, noting that

‘political attitudes are not random and unstable, neither are they constrained

along a single left-right dimension, instead they are structured within a value

framework involving dimensions of both left-right and libertarian-authoritarian

beliefs and possibly several others. When measured suitably these values appear

to form consistent, stable and consequential elements of British political

culture.’ [Heath and Lalljee 1996: 109]

Indeed, the general

uneasiness of the population in placing itself on the political scale, as well

as their fickleness in supporting and opposing different parties and groups, is

not a result of any supposedly inherent lack of knowledge, but rather of the

unyielding and contradictory categorizations they are forced into.

The

Science of filling pots with no bottom

One way of dealing

with the left-right difficulties has been to create political spectrum maps:

various graphs – sometimes simple, sometimes complicated – provide a series of different

parameters. Indeed, the study by Heath and Lalljee

used, as mentioned above, an ‘authoritarian’ vs. ‘libertarian’ graph. ‘Left’ and ‘right’ is purely seen as an economic issue, whereas social and idealistic preferences are mapped

differently. This is similar to the so-called ‘political compass’ (illustrated above), which is now used

widely – especially on the internet – to ascertain political stances.

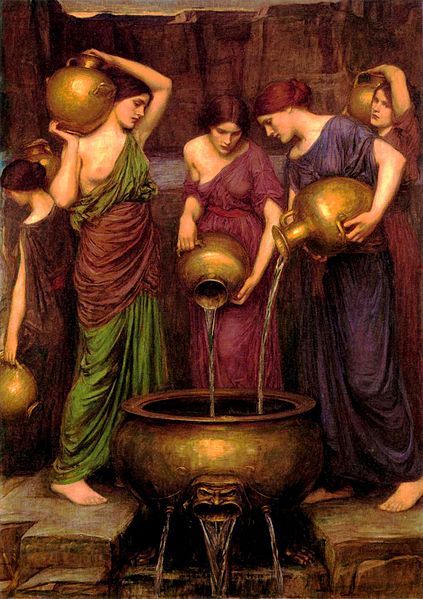

|

| Danaids |

Furthermore, the old

idea of ‘conservative’ vs. ‘progressive’, which is still widely used in the

characterization of right vs. left wing, also becomes useless if understood in economic terms like the graph

above – even contradictory. Whereas most economic policy today is Keynesian

(we’re all Keynesians now!), those who are generally labelled ‘fiscally

conservative’ are the ones who want to radically change, limit and decrease government involvement in fiscal matters, whereas those who are generally characterized as ‘progressive’ want to ‘conserve’

and further current economic models, arguing for maintained belief in

Keynesian socio-economic systems as well as resistance to new impulses of austerity, as prompted by the

world-wide financial crisis.

Opposed

Allies

Indeed, a quick look

at one of the main issues that currently dominates Western political debate, namely how to combat

the financial crisis and failing economies of the West, again reveals the futility, but also straight-out harmfulness, of

such a left-right divide. The left- and right-wing narratives seem, at first

sight, strongly opposed: while the former largely blames the crisis on the

extravagances and moral corruption of the banks, bankers and large

multinationals, the latter consider high tax-burden and mismanaged social

policies as the main culprits. The solutions proffered are also radically

different: one side wants to heavily regulate the banking sector (carrying

slogans saying ‘Capitalism has Failed!’) the other proposes lower taxes and

cutting social expenditure.

View

the difference

To illustrate this,

and to end this brief foray in some of our oldest political

terms, I have picked two videos – one from a left-wing background, one from a

right-wing background – which talk about the financial crisis. First, quite a

famous documentary, generally identified as ‘left-wing’, called ‘Inside Job’. In this documentary, though speckled

with typical ‘capitalism has failed’ and ‘the free market doesn’t

work’ narratives, the film-makers' research led them to the problem that so many of

the people responsible for the crisis were paid by, backed by, or even working

for, the government. A large part of the documentary is spent pointing out that many of the very same bankers which can be held responsible for the crisis

now occupy high positions in government.

A brief promotional clip can be found here, though the full documentary is of course copyrighted (go and watch it!):

The second clip, by

commentator and businessman Peter Schiff , shows Peter Schiff attending the

Occupy Wall Street protests when they were still in full swing, carrying a sign

reading ‘I am the one percent, let’s talk’. Though both

sides disagree on who exactly is the instigator of the financial troubles, near the end of the video (if you only watch two minutes, watch this) both sides seem to agree

on the problem, and invite each other to join their ranks. Strikingly, it ends by many of the Occupy movement expressing that they do not think capitalism is the problem.

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

Indeed, to briefly voice my personal opinion, ‘Inside Job’, though brilliant in bringing to the

fore some of the problems in our current system, sadly, because of the party-political façades and the dichotomy described above, falls into the exact same pitfall which has led to those responsible for the

crisis being in government. Seeing the negative effects the regulators have

had on our economy, the documentary pushes for more regulation and more ‘oversight’. Though their intentions are commendable, the thought that any political organ – something which exists only to support

certain political interests – could ever objectively govern the economy in the

interest of all, is sadly vain hope.

Only if every single

individual were directly represented in government, would the government realistically

protect every individual’s interests in economic policy. This is not possible through any sort of indirect representation, or financial committee. It is, however, exactly

what defines the free market: every single individual’s choices and preferences having

a direct input, and it is the collective – made up of millions and

millions of individuals – that decides which businesses are prospering

and which aren’t. Not some bureaucrat with vested interests. As long as we make sure

human rights and dignity are maintained and enforced across the board, the free market is the most egalitarian way of organizing the economy possible. As said in the video above by the Occupy protester, no

monopoly can ever rise without government interference (also said by Hayek[1944] p. 48 onwards). Many have been

conditioned to hate the free market. In this way, when government involvement fails, the establishment can claim it was because there was too little of it (leading to situations where those that failed the banks subsequently sat in government). The free market is, however, the fairest tool we have to organize our economy: too bad it has never been tried.

Come

Together, Right Now

Taking a step back now

from personal opinion, let us get to the point: the only reason those groups of the population that identify themselves as variously left- and right-wing are seemingly at opposite sides of the debate on the financial crisis, is because of the façade meticulously built up by those in power over the past centuries. Though different groups may disagree on the way the crisis started, all recognize what the problem is. Yet rather than attacking the problem, we limit ourselves to attacking each other. What is more, the current debate on the economy is just one of a myriad of issues where similar circumstances hold. It is time to leave antagonizing speech and characterizations behind, as well as void terms that do not even describe our real hopes and dreams, and for once start conversing clearly and straightforwardly with each other. Only then, will democracy truly thrive.

No comments:

Post a Comment